Centre researcher Wijnand Boonstra provides a summary of a recent study showing the importance considering historic junctions when explaining the development of social-ecological traps. Front cover photo: Wikipedia Commons

Poverty traps

Children of the involution

Why history matters in the creation of social-ecological traps

- Social-ecological traps are locked processes where natural resources are degraded and the people depending on them remain poor

- Piecemeal, incremental change will often not be sufficient to break out of such traps

- Knowing the effects of timing and history is of crucial importance for understanding, preventing and solving social-ecological traps

Everything happens for a reason and nothing comes from nothing. The same can be said of social-ecological traps, a locked process where natural resources are degraded and the people depending on them remain poor. Such traps are hard to escape. Piecemeal, incremental change will often not be sufficient to break out of them.

In a recently published paper in Ambio, centre researcher Wijnand Boonstra and Florianne de Boer, a graduate from Oxford University, demonstrate that the how depends crucially on the when.

"Knowing the effects of timing and history is of crucial importance not only for understanding but also possibly preventing and solving social-ecological traps," says Boonstra.

No background variable

He argues that most studies on traps treat history and timing as just a background variable in their analysis. To address this "hiatus", Boonstra and de Boer have studied the role of history and timing in four cases of social-ecological traps: agricultural involution in rural Java, the gilded trap in the Maine lobster fisheries, the dryland poverty trap in Makanya, Tanzania and the lock-in trap of the Western Australian agricultural region.

The first case study, agricultural involution in rural Java, is considered a classic example of how a sequence of distinct phases, or a path-dependent process, leads to social-ecological traps. The study of the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz, describes how, from 1619 to 1950, the conjunction of social and ecological processes on the island set in motion what Geertz famously called "agricultural involution", a term Boonstra and de Boer consider an early description of a social-ecological trap or a "gradual, deterministic process that got people trapped in poverty".

Geertz's study provides a comprehensive historical explanation to why rural families on Java kept on intensifying their already highly productive wet rice cultivation instead of expanding or modernising their farming styles. According to Geertz, the Javanese had too much tied up in the sawahs, the wet rice cultivation fields provided them with an extraordinarily stable output.

The ability to "squeeze just a little bit more out of even a mediocre sawah" created a typical 'sunk-cost effect', that is investing in something which is not sustainable in the long run. However, the sunk-cost effect alone is not sufficient to explain the persistent poverty in which farmers on Java where caught. According to Geertz' work two other factors have to be taken into account as well. The first factor was the Dutch colonisation of Java between 1619 and 1942. During this period, the Dutch imposed a plantation economy which was kept strictly separate from a Javanese subsistence economy. It meant that Javanese farmers did not have access to cash crops or global markets.

The third factor that contributed to the Javanese poverty trap was population growth. From the early 19th century the Javanese population grew from seven million people in 1830 to almost 42 million in 1930, which meant that any productivity increase through intensification of rice cultivation was quickly usurped by a growing and hungry population.

One damned thing after another?

The combination of these three factors created the "agricultural involution".

"Involution refers to the rigidisation of social and ecological interactions, which then become a trap and substantially limit human agency," Boonstra explains.

The conclusion of Boonstra and de Boer’s study is that history matters.

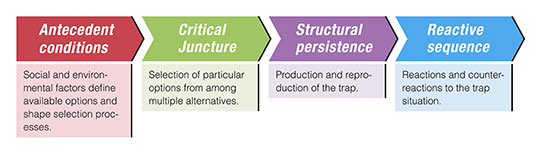

"Our study shows unmistakably the importance of conjunctions in time. These conjunctions become critical junctures which subsequently trigger the structural persistence of certain social-ecological dynamics,” Boonstra says.

"Hopefully there is no doubt after reading our paper that history is more than just "one damned thing after the other"", Boonstra concludes.

Illustration explaining the ideal–typical structure of a social–ecological trap.

Boonstra, W.J. and de Boer, F. 2014. The Historical Dynamics of Social–Ecological Traps. AMBIO, Volume 43, Issue 3 , pp 260-274. 10.1007/s13280-013-0419-1

Wijnand Boonstra is particularly interested in understanding how individual use of ecosystems aggregates to form so-called regimes of ecosystem use. Describing and explaining the complex set of social and ecological conditions and their interaction at micro and macro scales that cause these regimes to shift, is a key research objective.