Maja Schlüter explains her research on modelling social-ecological systems.

Meet our researchers

Modelling the workings of social-ecological systems

Centre researcher Maja Schlüter looks at how human-nature interactions shape success or failure in resource management

- Social-ecological systems are interdependent and complex adaptive systems

- Maja Schlüter's work focuses on understanding what drives change in these systems

- Identifying key aspects can help understand how to do sustainable resource management

We have to improve our understanding of social-ecological systems as truly interdependent and complex adaptive systems. This includes digging into the many micro-level interactions that occur between humans and ecosystems and identifying the mechanisms that explain why adaptation and change sometimes happen and sometimes does not.

This is the main focus of centre researcher Maja Schlüter’s work. Together with colleagues from both inside the centre and outside she develops ways of working with mathematical and computational models that can deal with the complexities and interdependencies of social-ecological systems.

“Ecological modelling studies often view humans as external disturbance or drivers of ecosystem processes while economic modelling studies often treat ecosystems only as input to a production process. Neither generally takes into account that humans and societies may or may not adapt their behaviour as a response to ecological changes, by for example decreasing the fishing pressure, and that this impacts on the ecological system and creates a new kind of feedback,“ says Maja Schlüter, as we’re sitting down for an interview to get to know her and her research a bit better.

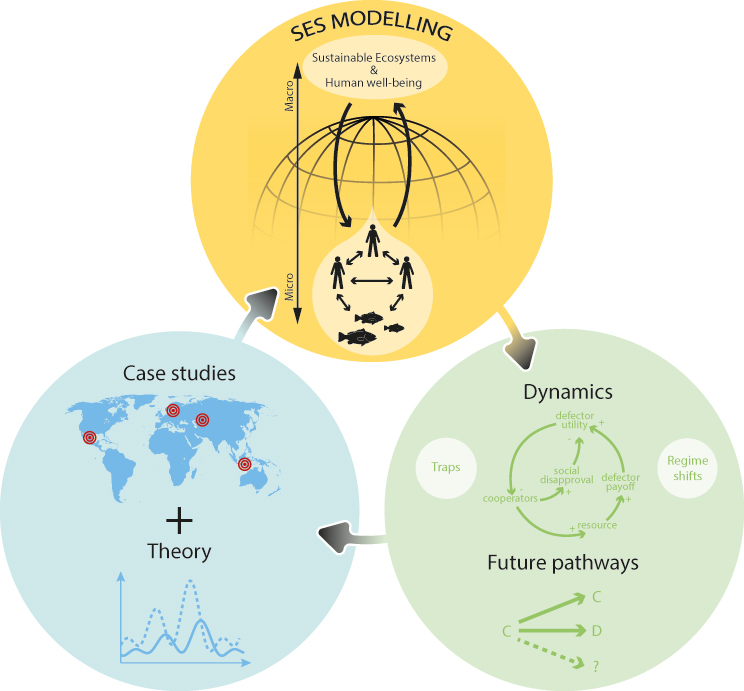

She studies what she describes as “the co-evolutionary dynamics of social-ecological systems.” These dynamics emerge from the actions and interactions of actors and ecosystems within a social-ecological system. The nature of these interactions, she explains can set the stage for phenomena such as regime shifts, traps or sustainable management.

Maja Schlüter. Photo: N. Björling/Kontinent

No longer neglecting important interactions

As we speak you are about to finish up SES-LINK, a five year long research project funded through a European Research Council (ERC) starting grant. What has been the focus of this project?

“In SES-LINK we have asked questions such as “Under which conditions do cooperative forms of self-governance emerge in small-scale fisheries?” and “How did social processes affect the ecological collapse in the Baltic?” Our goal has been to gain theoretical and practical insights about mechanisms of change or lack thereof, resilience and adaptability of social-ecological systems, especially in the context of natural resource management. We also want to contribute to further development of concepts and methods for an integrative analysis of these systems.”

What is it that drives your curiosity in research?

”I’ve always wanted to better understand how mutual adaptation of humans and ecosystems to perceived or real changes in the social-ecological system give rise to the complex dynamics and patterns. To this end we have developed a framework and empirical models where we investigate the importance of social-ecological systems to regime shifts or traps. For instance with a model of the Baltic Sea fisheries we can show that human adaptive behaviour slowed down the collapse of the cod in the 1980s,” Maja says.

She goes on to explain how these kinds of insights can be relevant for decision-makers:

“Though the research we do in my projects is aimed at theory development and not directly at policy recommendations, the insights we contribute can hopefully support the development of more integrative and effective policies that do justice to the complexity of the systems we manage.”

A more nuanced approach

Maja means that the increased understanding that her and her team want to contribute to, concerning what conditions create what kind of behaviours and responses in social-ecological systems, can enable a more nuanced approach towards developing policies and interventions that are better adapted to differences in the contexts where they apply.

It seems to me that SES-LINK asks quite big and almost abstract questions. How have you gone about finding answers to them?

“Yes, the questions we take on are quite big. Our approach involves a mix of methods from empirical, case-based research to theoretical, stylized models to simulations models that are based on empirical data. Based on knowledge from case studies we pose assumptions and hypotheses about social-ecological interactions and social and ecological processes that may be critical for explaining certain system behaviour such as a regime shift or a trap. We then systematically test these assumptions and hypotheses in our models”

By comparing the modelling results to empirical data the team then revisits the original understanding and hypotheses to improve on them and better understand the consequences of assumptions we make about social-ecological interactions. Through such a process the goal is to develop a more general understanding of key processes and interactions in different types of social-ecological systems.

During the course of the project Schlüter and her team have developed social-ecological models of the Baltic fisheries, cooperation in common pool resource management, lake restauration in Southern Sweden, small-scale fisheries in Mexico, and irrigation in Bali.

A conceptual figure illustrating the SES-LINK process for creating models and testing them against real world cases and data. Illustration: J. Lokrantz/Azote

No small task

The goal in the end is to find general patterns of social-ecological interactions that under certain conditions may lead to specific outcomes, such as sustainable management, thus finding explanations that are relevant for types of similar situations but still take into account particular contexts. Hopefully this may help to better understand what is needed to manage systems more sustainably.

This kind of modelling of social-ecological systems sounds like a project that requires a quite broad range of competences, how have you dealt with this?

“It is indeed. To be able to tackle these kinds of research questions and build dynamic models is no small task. In our work we rely strongly on cooperation with experts in different fields and with empirical researchers who know the real world examples we study very well. I find this way of working together really rewarding: It allows us to take on very interesting questions and the input from such varying expertise, in my view, is a way of ensuring that what we do is valid for the real world, even if it at times seems abstract and very theoretical, “says Maja.

In fact, she points out, this transdisciplinary and collaborative approach was one of the reasons she wanted to be based at the Stockholm Resilience Centre in the first place:

“In recent years more initiatives have cropped up, but the Stockholm Resilience Centre is still one of fairly few centres that do this type of research in Europe. Since my first encounter with the centre at the 2008 Resilience Conference, I’ve always liked the collaborative atmosphere and the way you can really feel how a group of people in a room inspire each other and jointly create insights that no individual could have if left to their own devices.”

While inspiring and interesting, do you find that this way of working also come with challenges?

“There are definitely challenges. Working with models in itself presents many challenges in for example choosing what variables and processes need to be included for the model to be valid and relevant, and then to find ways to compare model results to real world patterns. Then the transdisciplinary approach and integration of knowledge across disciplines and perspectives is no easy task. However, our team itself is very interdisciplinary and thanks to everybody’s openness and curiosity and constant willingness to understand and critically reflect on each other’s work we are able to develop cross-disciplinary understanding and awareness. This has been a tremendously rewarding experience.”

Finally, now that SES-LINK is coming to an end, what are your next steps?

“Fortunately this year I received an ERC consolidator grant which enables me and my team to continue this line of research for another five years. The new project is called MuSES and in it we will expand on the foundations we have built in SES-LINK but broaden the scope by including cross-scale interactions, for example markets or migration of species, in our analysis of local systems such as fisheries and agriculture and working at larger scales.