A new study argues that in landscapes where species such as the capercaillie compete for habitat availability with other birds, a ”multiobjective approach” can help them thrive at the same time. Photo: L. Nilsson/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

CONSERVATION STRATEGY

The art of compromising

Rather than maximising habitat availability for one species, more democratic solutions could benefit several at the same time

- Classic conservation strategy is to rank species based on their economic and ecological value. The consequence is that the conservation of one species may come at the cost of another

- Researchers push for a “multiobjective approach” when forced to make hard choices between different species

- The solution is to move away from maximising landscape capacity for one species, and apply a more democratic approach based on compromises

What does a capercaillie, flying squirrel, hazel grouse, long-tailed tit and two species of woodpeckers have in common? Quite a lot in fact. They not only share living space in Nordic boreal forests but their fundamental existence is in the hands of forest management policies and conservation strategies.

Classic conservation strategy uses a ranking system based on a species’ economic and ecological value. The consequence is that the conservation of one species may come at the cost of another, even if they are closely linked.

The irony is noticeable.

A new study written by centre researcher Adriano Mazziotta together with the research group of Prof. Mikko Mönkkönen from the Dept. of Biological and Environmental Science (University of Jyväskylä, Finland), Prof. Kaisa Miettinen (Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä) and with Dmitry Podkopaev from the Systems Research Institute (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland) argue that such an approach can be replaced with one where multiple species can thrive at the same time.

Mazziotta and his colleagues push for a "multiobjective approach" that can be used by land managers when forced to make hard choices between different species.

The approach, Mazziotta explains, is designed to maximise the landscape’s capacity to support biodiversity while limiting economic losses.

This approach can reduce conflicts among biodiversity objectives and offer room for synergies between several ecosystem services.

Adriano Mazziotta, lead author

Habitat adaptability and availability

In their study, the researchers looked at how six species found in a forest landscape in South Central Finland could be equally supported by forest management despite competing for the same space to live in. The species were the previously mentioned capercaillie, flying squirrel, hazel grouse, long-tailed tit, lesser-spotted woodpecker and the three-toed woodpecker. The researchers calculated habitat availability over a 50 years timespan, based on how the landscape would change due commercial timber operations.

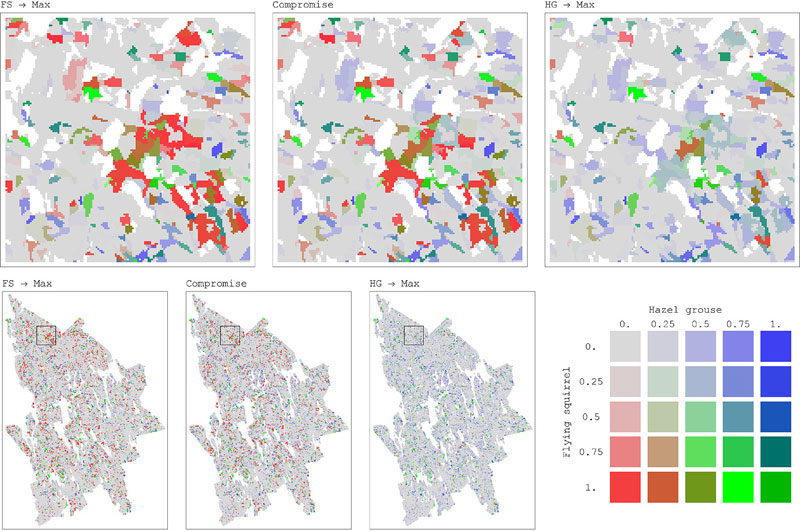

Although changes in habitat for some of the birds did not particularly affect the habitat of others, conflicts also occurred. The most compatible species were the capercaillie and the lesser-spotted woodpecker, while the other four showed both high and low conflict levels.

The researchers also found what they call an “asymmetric compatibility.” For instance, maximising habitat availability for the hazel grouse created strong conflict with maximising habitat for the flying squirrel, but not the other way around. This is because the management plan for maximising habitat is unique to each species.

So then, the question is; how to make all species happy?

Compromises with little negative effects

According to Mazziotta and his colleagues, the solution is to move away from management plans maximising landscape capacity for one species and apply a more democratic approach based on compromises

"This way, one species receives significant improvement of habitat availability at the expense of a relatively small deterioration of the other species’ habitat," he explains.

For example, finding a compromise between the flying squirrel and the hazel grouse increased habitat availability for both. In the end, a common approach was identified for all six species and each of them maintained at least 85% of their maximum landscape capacity.

Maps of distribution of habitat availability values for a pair of conflicting species, flying squirrel (FS) and hazel grouse (HG). Maps on top present magnification of regions, outlined in the map at the bottom left with black square borders). The color palette is defined by the ratio between habitat availability values of the two species. The intensity of the color corresponds to the absolute values of habitat availability. Color legend: red when habitat availability of FS is positive while habitat availability of HG is zero. Blue when habitat availability of HG is positive while habitat availability of FS is zero. Green when both species’ habitat availabilities are positive and “fairly” shared between them. Credit: Mazziotta et. al. 2017. Silva Fennica vol. 51 no. 1 article id 1778. Click on illustration to access article.

Capacity building needed

Mazziotta acknowledges that the approach is computer intensive and requires a "significant analytical capacity" which may not be readily available among land managers. Capacity building for land managers in this arena is needed.

"This study presents an alternative method to solve conservation conflicts at landscape level. However, landscape management is constrained by many aspects, including legal issues, financial constraints and organisational structure," Mazziotta says.

Given the future possible increase in conflicts between biodiversity objectives triggered by forestry intensification, there is much to gain from applying this multiobjective approach.

In fact, a general knowledge on the ecological species requirements was enough for Mazziotta and his colleagues to calculate potential habitat availability.

"This approach can reduce conflicts among biodiversity objectives and offer room for synergies between several ecosystem services," he concludes.

Methodology

Mazziotta and his colleagues developed new concepts and approaches to describe and measure conflicts among conservation objectives and for resolving them via multiobjective optimization. To measure conflicts they introduced a compatibility index that quantifies how much targeting a certain conservation objective affects the capacity of the landscape for providing another objective. To resolve such conflicts they found compromise solutions defined in terms of minimax regret, i.e. minimizing the maximum percentage of deterioration among conservation objectives. Finally, they applied the approach for a case study of management for biodiversity conservation and development in a forest landscape. They studied conflicts between six different forest species, and identified management solutions for simultaneously maintaining multiple species’ habitat while obtaining timber harvest revenues. They employed the method for resolving conflicts at a large landscape level across a long 50-years forest planning horizon.

Mazziotta A., Podkopaev D., Triviño M., Miettinen K., Pohjanmies T., Mönkkönen M. 2017. Quantifying and resolving conservation conflicts in forest landscapes via multiobjective optimization. Silva Fennica vol. 51 no. 1 article id 1778. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1778

Adriano Mazziotta focuses on evaluating the effects of climate change on biological systems, at different levels of complexity, spanning from genes to species to ecosystems.