Bildtext

Million Belay explains his research on how the food system in Ethiopia is changing, and finding desireable pathways to a sustainable food system that provides nutritious food.

Meet our researchers

Mapping the food system’s past, present and futures in Ethiopia

Million Belay combines research and policy work to understand an increasingly changing food system in Ethopia and advocate for a better food future

Text

Million Belay grew up in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. While his own childhood meals were diverse and nutritious, cooked from a variety of vegetables and fruits, he has watched the food system and people’s eating habits change over the years.

He now divides his time between research and policy work. He moves between studying how the food system in Ethiopia is changing and what is driving it to change while also coordinating one of the largest networks in Africa, Alliance for food sovereignty in Africa or AFSA for short.

“The ultimate goal is to advise policy makers to support a food system transformation which helps increase food production but also protects the health of the people and the earth,” he tells me over coffee. To reach this goal Million focuses his research on understanding how much and how fast the food system in Ethiopia is changing and finding what is shaping this change. He then wants to identify the desirable pathways to a sustainable food system that provides nutritious food.

“Once we can see the desirable pathways, the next step is to look for what is standing in the way of getting there, and find ways to get around or break down those blockages,” he says.

A woman pounding maize to make flour. Photo: V Mellegård

Quantity over quality

In recent years, he says, the Ethiopian government has adopted a productivity approach to food production where quantity takes precedence over everything else. As a result agriculture has intensified, with increasing use of chemical inputs like pesticides and synthetic fertilisers. There is also a decrease in the diversity of crops that farmers grow.

And the changing food system has consequences. As in the rest of the world, Ethiopia is seeing a rise in non-communicable diseases, with diabetes more prevalent than ever before. The possibility to maintain a varied and balanced diet is also decreasing for many people.

“These changes are affecting poor people the most,” he says. “Vegetables have become so expensive they are becoming difficult for people to afford, and many kinds of fruits are now luxury items that are out of reach for large part of the population. Since I was a child, the price of a kilo of a banana has increased at least 20 times.”

The singular focus on quantity in food production is a kind of crisis response aiming to ensure food security. Its narrative is that of needing to produce more food to provide for a growing population at any cost to avoid a food crisis.

“To achieve this increased productivity the strategies that are adopted in Ethiopia today most often focus on bringing in improved seed varieties alongside agrochemicals and irrigation systems,” Million says.

“Getting this kind of system to work has required changing the way farmers farm and the way they think about agriculture. It also requires prioritising business, which has meant focusing on high value crops, as well as changing both infrastructure and laws. In the end this narrative of focusing on increasing productivity alone has led to environmental damage and health problems, and it has contributed heavily to climate change”

Research can help us develop better, well grounded, scenarios for the future and identify paths that will take us in different directions. Based on this kind of understanding policy- and decision-makers can make better choices

- Million Belay

Mapping the food system

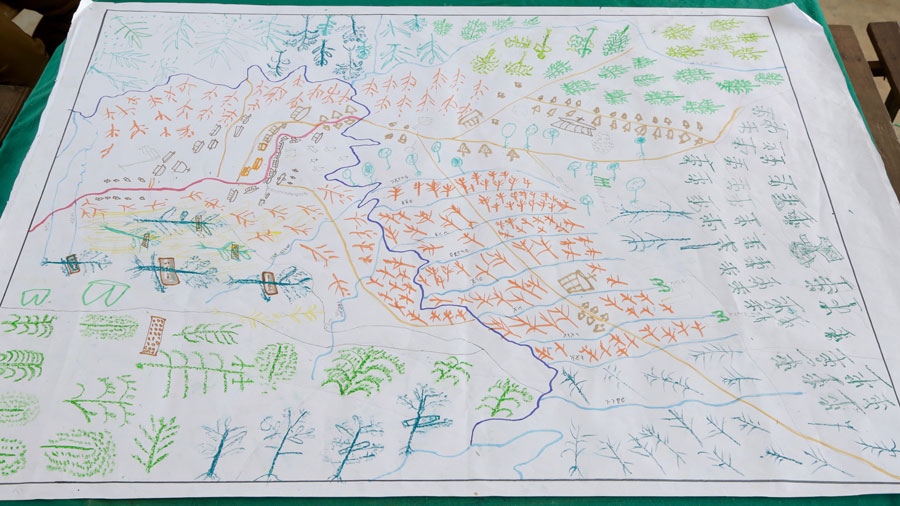

To understand the changes in the food system more deeply, Million uses a method called participatory mapping. The method produces maps that are based on people’s knowledge and understanding of their landscape, drawn from observation or memory. The mapping usually involves drawing symbols on large pieces of paper, to represent features in the landscape. It is not about producing or relying on exact measurement, but rather provides the participants with a channel for expressing connections to and cultural importance of a landscape.

Using a topographic map, from which everything except rivers and contours has been removed, allows people to orient themselves in their landscape and fill it with features representing for example the past, the present or a desirable future.

A map produced in a participatory mapping exercise. Photo: V. Mellgård

“Participants are asked to fill in the blanks on the map to produce the different scenarios. They map the past the way they remember it, and then the present to illustrate what has changed,” Million explains.

“For mapping the future we ask them to produce two different scenarios – one based on the assumption of that the food system will continue as it is operating today, and one based on what they would consider a better future.”

The two different maps of the future are then used to discuss the barriers to reaching that desired future.

“We ask the participants what are the rules, regulations and policies acting as barriers to this desired transformation, how we can engage with the barriers and what would be the most strategic place to start.”

Injera is a staple food in Ethiopia it is often made from teff. Here it is served with vegetarian toppings made from lentils, cabbage, spinach, shiró. I Photo: V. Mellegård

Getting to the desired future

The insights generated around how the food system is changing, and around what people consider to be desirable futures feeds into Millions policy work.

But bringing research and policy together is not an easy task. While the first requires you to to sit and read and think and produce, the second is ever changing, fast paced, and time consuming. “In research you deal with abstraction and abstracting, but in the policy space, you to bring that into daily language and into practice.”

Though it may be challenging, Million believes it is worth it and that research could help increase the credibility of policy decisions:

“Research can help us develop better, well grounded, scenarios for the future and identify paths that will take us in different directions. Based on this kind of understanding policy- and decision-makers can make better choices,” he says. “In this way research is critical for policy work – it gives you confidence, data and concrete cases to help guide decisions.”

Million Belay is part of the research team under the GRAID programme. His research focuses on using participatory methodologies, including participatory mapping, for social learning and change. He is an expert and advocate for forestry conservation, indigenous livelihoods and food and seed sovereignty

The photos in this piece are from a series featured on the sthlmresilience Instagram account, find more by following us there.