A new study published in PLOS, researchers demonstrate how megacities like Karachi are highly vulnerable to any changes in how rain finds its way to the city. Changes to the sources of their rainfall could have serious consequences for megacities’ supply of water. Photo: Bilalhassan88/Wikimedia Commons

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

URBANISATION AND WATER SUPPLY

A hard rain’s gonna fall

Amid an increase in megacities, changes in ecosystems far away can affect local access to freshwater

- Researchers have been able to identify the source of precipitation for 29 megacities around the world

- Changes to the sources of their rainfall could have serious consequences for megacities’ supply of water

- Issues about water security is also closely connected to complex geopolitical issues between countries

There is nothing modest about Karachi, Pakistan’s third largest city. It is considered the most populous, cosmopolitan, linguistically, ethnically, and religiously diverse city in Pakistan. With its 16 million inhabitants (a conservative estimate) it is also among the most populous cities in the world. That puts a strain on its freshwater consumption, especially since it is situated in an arid part of the world.

Finding the source of rain

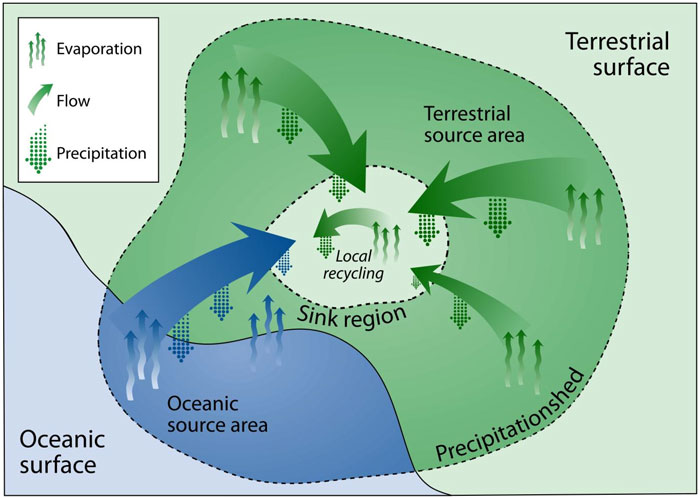

In a study recently published in PLOS, former centre PhD students Patrick Keys and Lan Wang-Erlandsson together with their supervisor, Associate Professor Line Gordon demonstrate how megacities like Karachi are highly vulnerable to any changes in how rain finds its way to the city. Changes to the sources of their rainfall could have serious consequences for megacities’ supply of water. In their study, the authors apply a previously developed method that helps locate where evaporated water starts its travel through the atmosphere and where it later falls as rain.

Request publication

Based on this work, they have been able to identify the source of precipitation for 29 megacities’ water supplies, around the world. 19 of these cities depend for more than a third of their water supply on evaporation from land, as opposed to evaporation from oceans. During dry periods this dependency could get even higher.

Megacities like Karachi can benefit from better knowledge about the interconnectedness of drastic land use changes in places far distant from the rivers on which their own water security depends

Line Gordon, co-author

"In many parts of the world, evaporation from land later returns to land as precipitation," Keys explains. On average, 40 % of precipitation on land originates from evaporation that came from land. An increasing amount of research shows that human-caused changes to landscapes such as large-scale forest clearing for crop production can significantly impact the amount of water that is evaporated into the atmosphere, and thus the amount of water available for rainfall.

Based on their method of locating the source of a city’s precipitation, Keys and his colleagues managed to backtrack 36 years of precipitation to the origins of evaporation, for each of the 29 selected megacities. In the case of Karachi, it almost fully relies on water from the Indus River, one of the longest rivers in Asia. However, a swelling regional population and poor water management makes the people of Karachi highly sensitive to changes in the precipitation falling in the Indus basin. "Karachi has very few buffers for its water supply," co-author Lan Wang-Erlandsson warns.

Amid geopolitical tension, more knowledge needed

A city’s vulnerability to water supply can also pose serious geopolitical challenges. Karachi for instance relies on water that stretches into the Himalaya and includes areas managed by India. Relations between India and Pakistan have been complex and largely hostile for decades. Similarly, Cairo, Egypt’s equally hot and bustling capital, is heavily dependent on water from the Blue Nile basin, whose most important tributary originates in Ethiopia – a country with whom Egypt has tense relations. As Ethiopia continues dramatic land-use change, Egypt will need to figure out how to manage their access to atmospheric water.

The researchers emphasize that their analysis must be seen as complimentary to other water vulnerability analyses, but argue that a better understanding about where water starts as evaporation to where it falls as rain can improve policies on urban water security.

"Our findings lead us to conclude that megacities like Karachi can benefit from better knowledge about the interconnectedness of drastic land use changes in places far distant from the rivers on which their own water security depends," Line Gordon says.

Methodology

Based on existing analysis of water scarcity among urban areas, we identified the surface watersheds for 29 urban areas containing 10+ million people. Using global climate data from 1979 to 2014 and the WAM-2layers moisture tracking scheme, we calculated the precipitationshed (i.e., source regions of precipitation) for each city, by tracking where evaporation enters the atmosphere, where it flows as water vapor, and where it eventually falls out as rain (this process is often referred to as moisture recycling). We further evaluated differences in the amount of water that comes from land, between dry and wet years. Finally, using pre-existing and new analysis, we calculated the vulnerability of each megacity’s moisture recycling, by examining existing surface water stress, economic capacity, potential for land-use change to impact moisture recycling, the sensitivity of moisture recycling to drier than normal conditions, and the buffers that megacities have in place to manage water resources.

Keys, P. W., Wang-Erlandsson, L., Gordon, L. J. 2018. Megacity precipitationsheds reveal tele-connected water security challenges. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0194311. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194311

Line Gordon is deputy director and deputy science director at the centre. Further to her managerial tasks, she is also assistant professor with a focus on freshwater resources, ecosystem services and food production