A new study looks at how ecologically connected Marine Protected Areas in Jamaica dealt with an invasion of the Indo-Pacific lionfish. Although the network succeeded in large part to connect various people across many sectors, it was also hampered by a lack of information sharing and collaboration. Photo: C.P. Ewing/Flickr

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

Marine Protected Areas

Fed to the lionfish

Invasion of the Indo-Pacific lionfish outside Jamaica reveals need to improve collaboration within marine protected areas

- Creating ways for individuals and groups to interact is a challenge within marine protected areas (MPAs)

- Study looks at how MPAs in Jamaica have collaborated to deal with the invasion of lionfish

- Trust is a necessary condition for successful collaboration

The fundamental purpose of marine protected areas (MPAs) is, as the name implies, to protect marine areas. That’s easier said than done. The establishment of MPAs often includes large geographical areas and a wide range of people from different institutions and policy sectors. In fact, this intricate network of people representing different interests could ultimately compromise the governance of an MPA.

How networks network

In a new study recently published in Aquatic Conservation, centre researchers Steven Alexander and Örjan Bodin along with colleagues from University of Waterloo, Canada, have looked at how collaboration between various people can improve the management of marine protected areas.

Alexander and his colleagues looked at how several ecologically connected MPAs in Jamaica dealt with an invasion of the Indo-Pacific lionfish. Specifically, they wanted to understand how various actors collaborated and shared knowledge about the consequences of the invasion. What they found was that although the network succeeded in large part to connect various people across many sectors, it was also hampered by a lack of culture of information sharing and collaboration. Limited financial resources also played its part.

High levels of trust between actors are one necessary condition for networks to persist and develop

Steven Alexander, lead author

Establishment of no-take areas

In 2008, the lionfish, a rather aggressive fish originally from the Indo-Pacific and Red Sea, were spotted in Jamaican waters, around Runaway Bay. With no natural predators, it quickly established itself around the island and consumed a significant amount of native fish.

Coinciding with this, the Jamaican government established 12 ’fish sanctuaries’ or marine no-take areas in 2009 to boost their conservation efforts around the island. The majority of these SFCAs were located close to several small coastal communities where fishing is a key source of income.

The SFCAs are co-management through partnerships between the national government and local NGOs and fisher cooperatives. Between them they had the responsibility to share the day-to-day management of the marine reserves. In total, 38 different organisations were found across the involved networks.

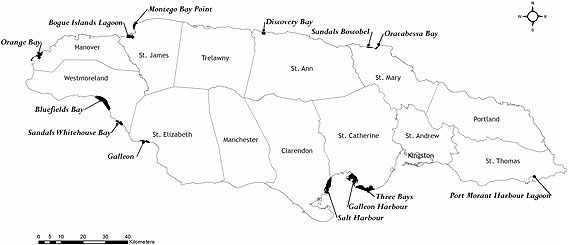

Special fishery conservation areas. Not shown here is the south west cay SFCA located at Pedro Bank, approximately 80 km south ofJamaica (map by D. Campbell). Click on map to access article

Why sharing or receiving ideas rarely happened

In their study, Steve Alexander and his colleagues looked at how the collaboration between the organisations worked out across national and local levels. All organisations were connected through a combination of formal partnerships, personal relationships and/or joint memberships on various committees, boards, and projects.

The analysis of the collaboration revealed several things including the fact that a lack of collaboration and sharing of information came down to – in part – competition for the limited resources and a lack of support for regular face-to-face meetings. As a consequence, sharing or receiving ideas rarely happened. On a national level, there was also little coordination between ministries, departments, and agencies, something which Alexander and his colleagues consider critical to improve the management of an MPA network.

”The general lack of linkages at the national level in Jamaica is worrisome if the aim is to increase coordination,” Alexander says. ”Moreover, there is little evidence to suggest that this has been effectively addressed or alleviated to date.”

However, the findings suggest that the presence of strong vertical ties from local organizations to national agencies facilitated an important flow of information. This led the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries to implement new legislation that re-designated them as ‘special fishery conservation areas.’ Importantly, this new designation included the necessary permissions and regulations to effectively remove invasive species.

Trust or bust

Collaboration within the many MPAs is still not perfect in Jamaica but the slowly improving coordination among the network is a source of cautious optimism. Amid the lack of face-to-face meetings and a prevailing competition between various groups, one thing needs to improve: trust among the parties involved.

”High levels of trust between actors are one necessary condition for networks to persist and develop,” Alexander says. This takes time, which is why face-to-face meetings are so important.

”Trust ultimately facilitates communication and collaboration, sets the stage for establishing common rules and norms, and helps to overcome instances where there is a lack of a culture of sharing and collaboration.”

There is also little doubt that the concept of multilevel collaboration, or institutions and individuals working across national, local and functional borders, is an increasingly important ingredient in dealing with environmental problems. This research could help along the way, co-author Örjan Bodin concludes: ”Managers, agencies, and organisations could gain important insights into relevant barriers and opportunities that exist within these networks.”

Methodology

This study employed a mixed methods approach including a sociometric survey, semi‐structured interviews, and document review. Data were collected over five months of fieldwork between November 2012 and February 2015, with the majority of data collection taking place from August 2013 to November 2013. Participants were provided with a roster of organizations and agencies and asked to identify the presence or absence of relational ties to each. Specifically, participants were asked to consider three different types of organizational ties: (1) information sharing; (2) managementoriented; and (3) collaboration. In addition, ‘name interpreter’ questions were used to elicit responses on the strength of the ties. Participants were also given the opportunity to add organizations and agencies not included on the roster with whom they had relevant ties. Interviews continued until the majority of relevant governance organizations had been sampled.

Alexander, S. M., Armitage,D. Carrington, P., Bodin, Ö.2017. Examining horizontal and vertical social ties to achieve social–ecological fit in an emerging marine reserve network. Aquatic Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst DOI: 10.1002/aqc.2775

Steven Alexander’s research focuses on community-based conservation and natural resource management, environmental governance, and the human dimensions of environmental change.

Örjan Bodin combines and integrates methods and theories from several scientific disciplines to develop better understanding of social-ecological systems.