A new study finds that in the places where fishers communicated with their competitors about the fishing gear they use, locations for hunting, and fishing rules, there were more fish in the sea—and of higher quality. Photo: J. Cinner/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

fisheries management

Breaking bread with rivals

When fishers collaborate with their fiercest competitors they can improve fish stocks on coral reefs

- A new study published in Nature Communication looks at the relationships between competing fishers, the fish species they hunt, and their local reefs.

- It found that in the places where fishers communicated with their competitors there were more fish in the sea—and of higher quality

- These relationships also help build trust, and can enable people to develop a shared commitment to managing resources sustainably

Environmental problems are messy. They often involve several interconnected resources and a lot of different people—each with their own unique relationship to nature. Understanding who should cooperate with whom in different contexts and to address different types of environmental problems is becoming increasingly important.

Better collaboration, higher fish quality

A new study published in Nature Communication looks at the relationships between competing fishers, the fish species they hunt, and their local reefs. Centre researcher Örjan Bodin is among the co-authors. The study is led by Michele Barnes, a senior research fellow from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University. Barnes and her team interviewed 648 fishers and gathered underwater visual data of reef conditions across five coral reef fishing communities in Kenya.

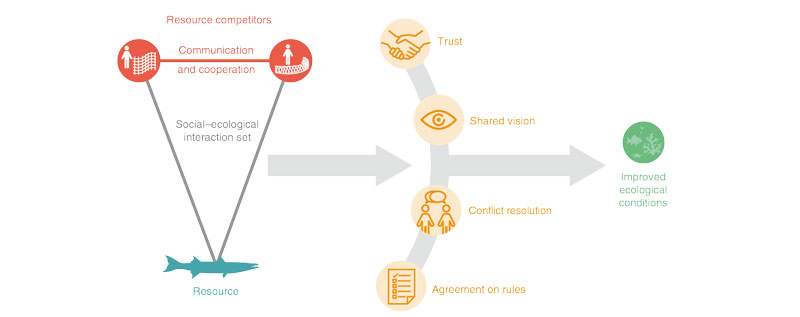

They found that in the places where fishers communicated with their competitors about the fishing gear they use, locations for hunting, and fishing rules, there were more fish in the sea—and of higher quality. These relationships also help build trust, and can enable people to develop a shared commitment to managing resources sustainably.

Barnes explains that relationships between people have important consequences for the long-term availability of the natural resources we depend on.

Our results suggest that when fishers—specifically those in competition with one another—communicate and cooperate over local environmental problems, they can improve the quality and quantity of fish on coral reefs.

Michele Barnes, lead author

Helps building trust

Co-author Prof Nick Graham, from Lancaster University, adds: “Across the world coral reefs are severely degraded by climate change, the pervasive impacts of poor water quality, and heavy fishing pressure. Our findings provide important insights on how fish communities can be improved, even on the reefs where they are sought.”

Co-author Dr Jack Kittinger, Senior Director at Conservation International’s Center for Oceans, says this is likely because such cooperative relationships among those who compete for a shared resource—such as fish—create opportunities to engage in mutually beneficial activities. These relationships also help build trust, and can enable people to develop a shared commitment to managing resources sustainably.

“This is why communication is so critical,” says Dr Kittinger. “Developing sustained commitments, such as agreements on rules and setting up conflict resolution mechanisms, are key to the local management of reefs.”

“The study demonstrates that the positive effect of communication does not necessarily appear when just anyone in a fishing community communicates – this only applies to fishers competing over the same fish species,” adds co-author and centre researcher Örjan Bodin.

A conceptual diagram illustrating key social processestheoretically supported by social–ecological network closure that may lead to improved ecological conditions in the commons. Click on illustration to access scientific study.

A framework that can be applied elsewhere

The study advances a framework that can be applied to other complex environmental problems, where environmental conditions depend on the relationships between people and nature.

Co-author Dr Orou Gaoue, from the University of Tennessee Knoxville, emphasises the broad appeal of the results.

“Although this study is on coral reefs, the results are also relevant for terrestrial ecosystems where, in the absence of cooperation, competition for non-timber forest products can quickly lead to depletion even when locals have detailed ecological knowledge of their environment.”

Methodology

To support their inquiry of the role of social–ecological network closure on ecological conditions in reef fishing communities, the researchers accounted for biophysical, environmental, and human impact characteristics known to effect reef ecosystem conditions. They also evaluated other social and institutional conditions known to effect collective management of the commons to determine whether they provided alternative explanations for the relative ecological condition of some sites versus others. Finally, they conducted a preliminary assessment of indicators of the key social processes supported by social–ecological network closure across sites to explore whether they aligned with our theoretical

expectations.

Barnes, M., Bodin, Ö., McClanahan T., Kittinger, J., Hoey A., Gaoue, O., Graham, N. 2019. ‘Social-ecological alignment and ecological conditions in coral reefs’. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-09994-1

In his work, Örjan Bodin uses and develops theoretical/conceptual models and simulations, as well as engaging in empirical studies and empirical data analyses. Bodin often describes and models social, ecological, and coupled social-ecological systems as complex and intricate webs of interactions between, and among, different ecological and/or social components.