Overfishing

We know what you've been up to

How China under-report fish catches in foreign waters

- Experts suspect that catches reported by China to the

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are too low - There are no publicly accessible databases of access agreements between China and the countries where their vessels operate

- The FAO should not only insist on proper reporting of catches from China, but the European Parliament should also encourage the funding of

research that focuses on China's international fisheries

When it comes to the future of marine ecosystems worldwide, few countries are as influential as China. It has the largest distant water fishing fleet, produces the majority of the world's aquaculture and is the dominant market for a growing number of seafood species.

Yet fisheries experts have long suspected that the catches reported by China to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) are too low.

Secret and unreported

In a new article published in the journal Fish and Fisheries, a team of international scientists including centre researcher Henrik Österblom, has attempted to estimate the distant water fleet catch by Chinese vessels between 2000 and 2011.

Österblom explains that there are no publicly accessible databases of access agreements between China and the countries where their vessels operate. Consequently, even if they could be perfectly legal, the activities and catches of the fleets are, in the public eye, almost completely undocumented and unreported.

"At the onset of the 21st century, China has become a global superpower in distant-water fishing. Unfortunately, the tendency to keep fisheries data secret has prevailed"

Henrik Österblom, co-author

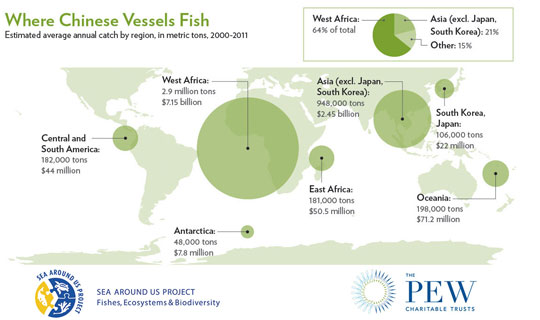

Amid the high degree of uncertainty, Österblom and his colleagues estimated that China catch more than 4.6 million tons of fish per year, which is in stark contrast to the 368,000 tons officially reported to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

Methodology

Without transparent and official public records, Österblom and his colleagues had to rely on data from non-official sources such as media reports, research articles and various websites. Together they collected over 500 sources with records from 93 countries.

Based on the data from these sources, a five-step catch estimation procedure was implemented. This procedure identified 1) where the vessels operated, 2) the number of vessels operating, 3) their estimated individual catch, 4) the geographical scope of these activities and 5) how this totaled at a global scale.

The data showed that the only large regions of the world where Chinese distant-water vessels do not appear to operate are in the Arctic, around the coasts of North America, in the Caribbean and European waters. The analysis clearly indicated that Chinese fleets extract the largest catch in African waters.

Österblom and his colleagues stress the importance of acknowledging the uncertainty surrounding their data.

"Given the high degree of uncertainty from our sources, we deliberately used an approach that yielded results that were very conservative and strongly biased downward."

To improve the transparency of the activities of distant-water fleets, Österblom and colleagues suggests some specific policy recommendations:

The FAO should not only insist on proper reporting of catches from China, but the European Parliament should also encourage the funding of research that focuses on China's international fisheries.

Not just China, though

However, Österblom and his colleagues also point out that such studies must be conducted as part of a broader international study. Otherwise the necessary dialogue with Chinese authorities would be burdened by the suspicion that Chinas is being singled out for practices, which unfortunately are widespread.

"The European Parliament and other international institutions should encourage full disclosure about the ownership of distant-water fleets because the complexity of re-flagged of vessels and use of flags of convenience, complex charters and joint ventures activities, and sometimes well-organized illegal activities associated with distant water fishing, tend to obscure and mask fishing operations to the extent that tracking real trends and designing policy interventions can become impossible," Österblom concludes.

Estimated average catch by Chinese vessels. Click illustration to enlarge. Illustration: Sue-Lyn Erbeck/The Pew Charitable Trusts

references

Pauly, D., Belhabib, D., Blomeyer, R., Cheung, W. W. W. L., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Copeland, D., Harper, S., Lam, V. W. Y., Mai, Y., Le Manach, F., Österblom, H., Mok, K. M., van der Meer, L., Sanz, A., Shon, S., Sumaila, U. R., Swartz, W., Watson, R., Zhai, Y. and Zeller, D. (2013), China's distant-water fisheries in the 21st century. Fish and Fisheries. doi: 10.1111/faf.12032

Henrik Österblom is a Deputy Science Director at the Stockholm Resilience Centre. His three primary research interests are 1) Social-ecological dynamics of the Baltic Sea, 2) International marine governance and 3) Seabirds and ecosystem change.