According to a paper recently published in Sustainable Earth, cities will ultimately fail in their ability to let people interact unless they integrate a better thinking around sustainability. The paper argues that cities depend on a healthy environment to function in a proper way. Photo: N. Ryrholm/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

URBANISATION

Healthy cities, healthy people

Not enough city dwellers are exposed to nature in cities. That could have serious impacts on their health

- Previously, poor sanitation, significant air pollution and low water quality created serious health issues for people living in cities. Today, these problems have been replaced by obesity and stress

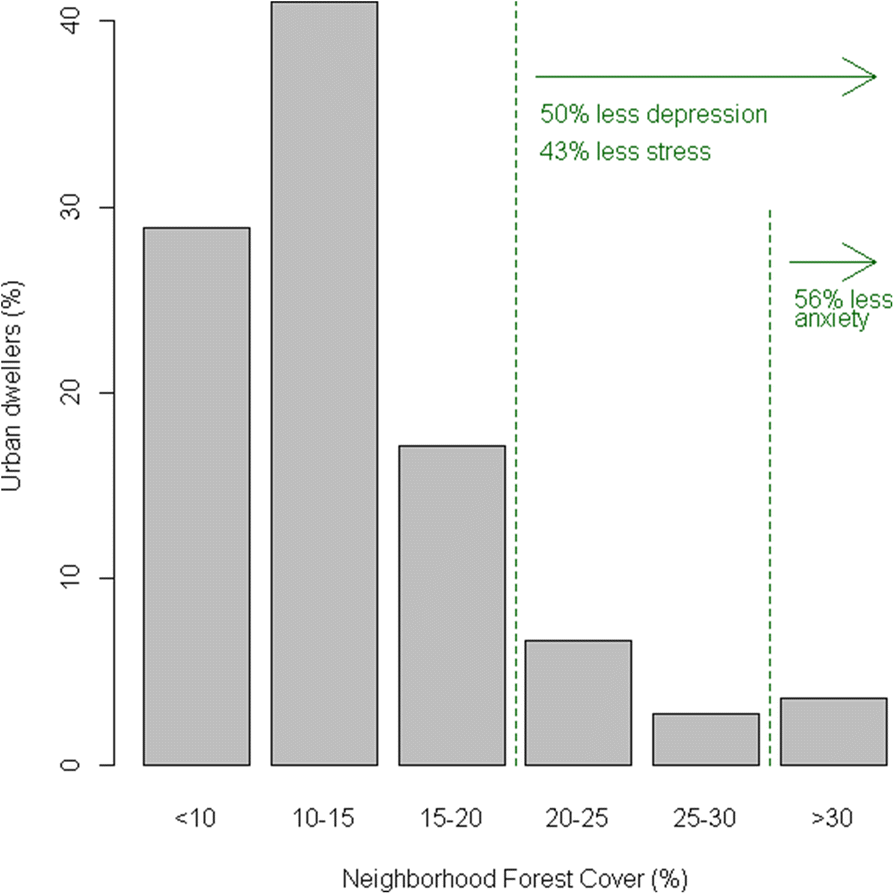

- Currently, only 13% of urban dwellers are living in neighbourhoods with more than 20% forest cover, the threshold found to be needed to protect against depression, stress and anxiety

- Nature-based solutions can mitigate several of the problems faced by people in cities

Cities are in many ways perfect for people. Thanks to increased proximity they are better able to let people share, interact and benefit from different services and relations. Yet environmental problems also make cities shockingly inhumane. Important ecosystem services such as drinking water protection, heat wave mitigation and recreation are increasingly compromised because urbanization is eating up the natural environment around cities.

New troubles in town

According to a paper recently published in Sustainable Earth, cities will ultimately fail in their ability to let people interact unless they integrate a better thinking around sustainability. The paper, co-authored by centre researcher Thomas Elmqvist, argues that cities depend on a healthy environment to function in a proper way.

Request publication

Previously, poor sanitation, air pollution and low water quality created serious health issues for people living in cities. Today, these problems have been replaced by challenges such as obesity and stress. The combination of calorie-rich foods and limited physical activity have made city people more obese compared to their fellows in more rural settings. Similarly, aspects of mental health appears to be persistently worse in urban areas than in rural ones. This is largely because of higher levels of noise and social density. The latter, according to Elmqvist and his colleagues is not without a certain irony.

It is ironic that the same phenomenon, cities’ capacity to increase interaction, is what makes cities both great and inhumane at the same time

Thomas Elmqvist, co-author

Nature-based solutions

How can cities remain hubs for continued social and economic benefits? This is where nature comes in, according to Elmqvist and his colleagues.

Nature-based solutions, or actions that are inspired by, supported by or copied from nature in order to address various social challenges, are considered crucial in order to mitigate several of the problems faced by people in cities. For example, natural habitats and wetland features can reduce flood risk. Conservation actions upstream in a city’s source watershed can maintain good water quality. Street trees and parks can improve air quality and reduce temperatures thus reduce the urban heat island effect. Many of these ecosystem services can have direct impact on peoples’ health.

Parks, in particular, can encourage recreation and physical activity. Research has shown how children who lived close to a park had lower Body Mass Index and better health compared to those who did not. Similarly, spending time in a natural environment can reduce stress.

Forest cover in urban neighborhoods and its impact on mental health. The bar chart shows the fraction of urban dwellers who live in neighborhoods with varying levels of forest cover. Forest cover was estimated for 1-km square neighborhoods in 245 major cities globally, as part of the Planting Healthy Air report [81]. The green lines shows thresholds in vegetative cover and its relationship to mental health, as identified by Cox et al. [102], who surveyed 263 respondents in three towns in the United Kingdom. They found that the odds-ratio of depression, stress, or anxiety being reported was significantly higher when houses had less than these thresholds of vegetative cover in the 250 m around their home

Not enough nature to go around

But is there enough nature in cities? According to the authors, the answer is no. Currently, only 13% of urban dwellers are living in neighbourhoods with more than 20% forest cover, the threshold found to be needed to protect against depression, stress and anxiety.

"Our results suggest that most urban dwellers are living in environments with low levels of nature exposure and may thus be at greater risk of mental distress," Elmqvist explains.

This is serious because the effects may be contrary to the benefits urban areas are supposed to provide.

"Our new urban world, while representing something quintessentially human, also is shockingly unnatural, likely negatively affecting mental health," Elmqvist continues.

A closer connection to nature can prevent this and there are initiatives out there which deserves consideration elsewhere. The Green Prescription programme in New Zealand is one example. Through subscriptions based on increased outdoor activity, public health and mortality has gone down. Similarly, it is important that cities grow and develop in ways that protect and grow nature, that put nature at the core of design and planning.

Despite challenges, green thinking is justifiable

But there are also significant obstacles to this vision, something Elmqvist and his colleagues acknowledge. For instance, reconnecting urbanites to nature through sustainable urban design works well in the developed world but is largely unrealistic in poorer countries. It can also create unintended consequences such as higher housing prices and gentrification. Still, many elements of this “biophilic” thinking is justifiable and applicable, particularly at the local level of urban areas.

“We believe that investments in urban trees, ecoroofs, green terraces and other forms of biophilic design will reap great benefits both in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and improve peoples’ health."

“Nature in cities allows us to have the benefits of urbanization while also having liveable cities in which we can thrive,” the authors conclude.

Link to publication

Request publication

McDonald, R.I., Beatley, T., Elmqvist, T. 2018. The green soul of the concrete jungle: the urban century, the urban psychological penalty, and the role of nature. Sustainable Earth 2018 1:3, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42055-018-0002-5

Thomas Elmqvist is a professor in Natural Resource Management at the Stockholm Resilience Centre. His research is focused on ecosystem services, land use change, urbanization, natural disturbances and components of resilience including the role of social institutions.