An increasingly large share of the planet’s biosphere has been modified in order to harvest, trade and consume as much food, fibre and fuel as possible. This is the gist of a new study published in Nature as part of the journal’s 150th anniversary collection. Photo: N. Ryrholm/Azote

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

THE ANTHROPOCENE

An altered planetary anatomy

Humans have transformed much of the planet to produce more and more food, fibre and fuel, now we need to radically transform this global production ecosystem. Centre researchers offer perspectives in Nature's exclusive 150th anniversary collection

- An increasingly large share of the planet’s biosphere has been modified in order to harvest, trade and consume as much food, fibre and fuel as possible

- The resulting ‘global production ecosystem’ has become too connected and simplified, with new and more pervasive global risks as a result

- Three solutions strategies are suggested for improved sustainability: redirection of finance, increased supply chain transparency, and participation of ‘keystone’ multinational corporations

(Swedish summary below)

Farming, forestry and fisheries are changing the anatomy of the biosphere. This makes us all more vulnerable to new types of global risks that will affect the long-term ability to provide food, fibres and fuel to a growing and wealthier human population.

This is the gist of a new study published in Nature as part of the journal’s 150th anniversary collection, featuring a selection of articles that “reflect the past, present and future of Nature”.

The article is written by a team of centre researchers, with Magnus Nyström as lead author, together with Jean-Baptiste Jouffray, Albert Norström, Beatrice Crona, Peter Søgaard Jørgensen, Örjan Bodin, Victor Galaz and Carl Folke, as well as Professor Steve Carpenter from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, USA.

The study notes that more than 75 per cent of the world’s land area has already been converted into domains like cities, farmland and timber-producing forests. In the oceans, around 90 per cent of fish-stocks are either overexploited or fully exploited while a rapidly growing aquaculture sector is taking up more coastal and offshore space than ever.

As available productive land and abundant fish stocks become progressively scarce, the potential for further land conversion, land redistribution and exploitation of new wild stocks as options to meet projected global human demand is dwindling.

Magnus Nyström, lead author

A “simplified” global production ecosystem

Historically, humans have converted forests, lakes and other natural ecosystems into simplified production systems like croplands, forest plantations and fish farms. This has been carried out with a focus on efficiency and the massive use of inputs such as fossil fuels, fertilizers, pesticides, antibiotics and technology. In parallel, people, places, cultures and economies have become increasingly intertwined across the world, making production ecosystems globally interconnected through international trade and the global market.

Taken together, these changes are gradually converting the biosphere into a “simplified” global production ecosystem that focuses on a small number of harvestable species. For example, pigs and chickens account for 40% and 34%, respectively, of all the meat production in the world, whereas more than 80% of the global fish and shellfish aquaculture production is sourced from 30 “staple” species. Even seemingly unaffected parts of the biosphere are under human influence.

“Subsistence fishing and farming or diversified agricultural landscapes, may be subject to little human input or export-mediated connectivity from international trade. Nevertheless, they are increasingly shaped by a broader set of global drivers, such as policies, technologies and economic changes”, the authors note.

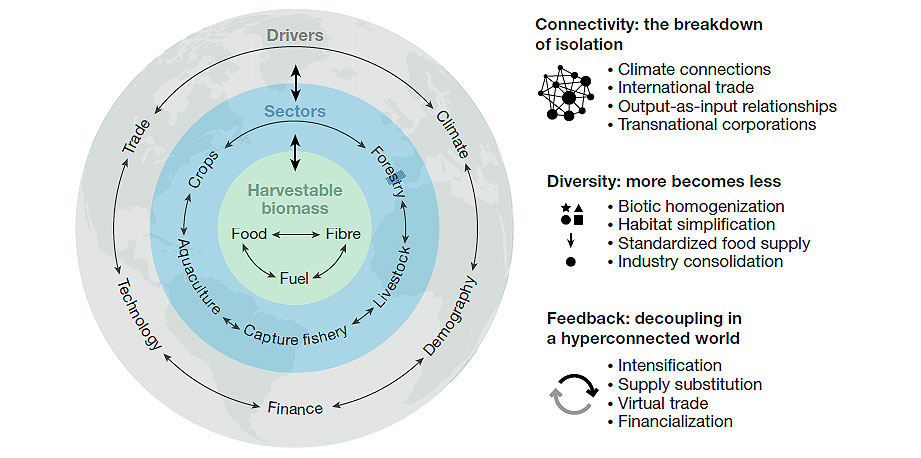

The global production ecosystem. The GPE is characterized by tightlycoupled relationships and reciprocal influence within and betweenharvestable biomass (green inner circle), multiple sectors (blue middle circle)and a broad set of distal drivers (grey outer circle). To the right are the threelenses (connectivity, diversity and feedback) and their key features throughwhich the anatomy of the GPE is described in this paper. Click on illustration to access the paper.

Increasing vulnerability and interconnected risks

The new global anatomy described above is already changing the global risk pattern. Shocks that were previously occurring locally within one sector are becoming “globally contagious” and more prevalent as sectors are intensified and more intertwined.

For example, droughts or crop pest outbreaks can spill over to seafood production, since fish farms increasingly depend on agricultural crops to produce their feeds.

“The hyperconnectivity and homogeneity of the global production ecosystem […] creates novel conditions for risks to emerge and interact, rendering our ability to produce harvestable biomass more vulnerable to disturbance,” the authors write.

This means that the capacity of the global production ecosystem to satisfy human demand for food, fibre and fuel will be determined by the consequences of these emergent risks.

Three avenues forward

The fragile anatomy of the global system for production of biomass is one of the grand challenges facing humanity, the authors conclude. To change course, the researchers suggest three overarching strategies:

- Redirecting finance for sustainability, exemplified by actions like divestment from unsustainable palm oil production, the insurance sector refusing to insure fishing vessels involved in illegal fishing, and banks denying loans to clients that do not comply with sustainability standards.

- Radical transparency and traceability, governmental policies that ensure that social and environmental criteria are met along whole supply chains. It also requires education and information to consumers in the form of certification, labelling and public campaigns.

- Keystone actors as agents of change, the handful of large transnational corporations that currently dominate agriculture, forestry and fisheries. In this context, the study also calls for improved science–business partnerships to complement public policies and governmental regulations. One example is the Seafood Business for Ocean Stewardship (SeaBOS) initiative, in which centre researchers directly engage with ten of the world’s largest seafood companies to influence their 600 subsidiaries with operations in at least 90 different countries.

But the researchers warn that the three strategies will never be successful without profound shifts in worldviews and belief systems.

“Ultimately, moving towards a more sustainable global production ecosystem is likely to require radical shifts in deeply held values, educational systems, and social behaviour that underpin current economic paradigms, consumption patterns and power relationships,” they write.

Svensk sammanfattning

I studien sammanfattar en svensk forskargrupp läget för världens samlade produktion av livsmedel, fibrer och bränsle, och konstaterar att:

• En allt större del av planetens biosfär har modifierats för att producera så mycket mat, fibrer och bränsle som möjligt

• Det resulterande 'globala produktionsekosystemet' har blivit för intensivt, förenklat och globalt sammankopplat - med nya och allvarligare globala risker som följd

• Tre lösningsstrategier föreslås för förbättrad hållbarhet: förändringar av finanssektorn, ökad transparens i leverantörskedjor och deltagande från ’keystone actors' (multinationella företag med stort inflytande)

Det alltför ensidiga fokuset på ökad produktion i jordbruk, skogsbruk och fiske/fiskodlingar har förändrat hela biosfärens anatomi, menar forskarna. Detta gör oss alla mer sårbara för klimatförändringar och andra nya typer av globala risker som kommer att påverka den långsiktiga förmågan att tillhandahålla mat, fibrer och bränsle till en växande världsbefolkning med ökad välfärd.

Detta är huvudbudskapet i en ny studie publicerad i Natures 150-års jubileumssamling, med ett urval av artiklar som speglar tidskriftens förflutna, nutid och framtid.

Artikeln är skriven av ett team av svenska forskare från Stockholm Resilience Centre samt GEDB-programmet och Beijerinstitutet vid Kungliga Vetenskapsakademin. Magnus Nyström är huvudförfattare, tillsammans med Jean-Baptiste Jouffray, Albert Norström, Beatrice Crona, Peter Søgaard Jørgensen, Örjan Bodin, Victor Galaz och Carl Folke, samt Professor Steve Carpenter från University of Wisconsin – Madison, USA.

Nyström, J.-B. Jouffray, A. V. Norström, B. Crona, P. Søgaard-Jørgensen, S. R. Carpenter, Ö. Bodin, V. Galaz, C. Folke. 2019. Anatomy and resilience of the global production ecosystem. Nature, Volume 575, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1712-3