DEALING WITH UNCERTAINTY

Why designing policies for extreme events requires a system overview

While low-cost, rapid responses to extreme events are needed, proactive measures are more important

- A new analysis explores governance approaches likely to reduce risk from extreme events

- Low-cost, rapid responses to extreme events are not enough, solutions must include investment in higher-cost systemic responses

- With radical uncertainty in the Anthropocene, societies must be allowed to transform to more resilient systems (through adaptive governance)

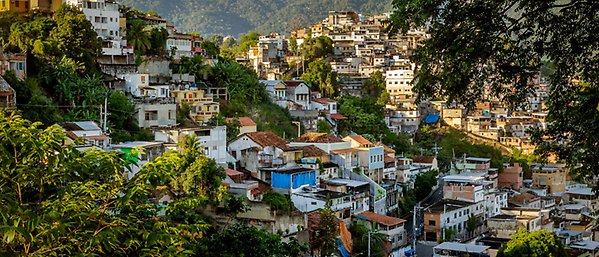

EXTREME EVENTS AND CORRESPONDING MEASURES: From pandemics to floods and heatwaves, extreme events are becoming more frequent as a result of human action like burning fossil fuels or encroachment into forests.

A new analysis by an international team of researchers explores governance approaches likely to reduce risk from extreme events.

Stop putting all eggs in one basket

The authors argue in the journal Ecosystems that low-cost, rapid responses to extreme events, while necessary, are not enough to address the problem. Solutions must include investment in higher-cost systemic responses. The paper is the result of the annual Askö meetings organised by centre partner Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics.

Designing policies for extreme events requires a system overview.

Simon Levin, lead author

Ultimately this means preparing to respond when a flood or heat wave strikes. Solutions range from adequate emergency response to efficient systems to distribute insurance payments.

But even if the proactive measures are often more important, governments struggle to prioritise them, for example a better global disease monitoring system would likely have reduced the impact of Covid-19, even if they allow societies to recover faster. This could be, for example by having a diverse economy producing a range of products rather than “putting all eggs in one basket” or ensuring adequate insurance protection in the first place.

Given the radical uncertainty in the Anthropocene, this must also mean ensuring the systems are in place to allow societies to transform to more resilient systems (through adaptive governance) in the future.

Clashing with needs of efficiency

The authors, including the Stockholm Resilience Centre’s science director Carl Folke write, “One potential strategy is to invest in general resilience”.

General resilience includes diversity but also redundancy (instead of one highway from one place to another, there might be several roads) and modular organization.

However, they recognize general resilience “is a costly public good that will erode if not actively supported”. Part of the problem is that it often clashes with the economic design principle of efficiency. This needs to change because the authors warn, “failure to maintain general resilience may greatly increase the economic and human costs of extreme events and disasters.”

Ultimately, extreme event management this century will often be about water – too little or too much. Throughout history, water management has been a make or break issue for governments.

As this century proceeds, the world can expect increasingly erratic flooding and droughts to become more common place. A full systems view of the challenge means governance to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to manageable levels as soon as possible.

Levin, S.A., Anderies, J.M., Adger, N. et al. Governance in the Face of Extreme Events: Lessons from Evolutionary Processes for Structuring Interventions, and the Need to Go Beyond. Ecosystems (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-021-00680-2