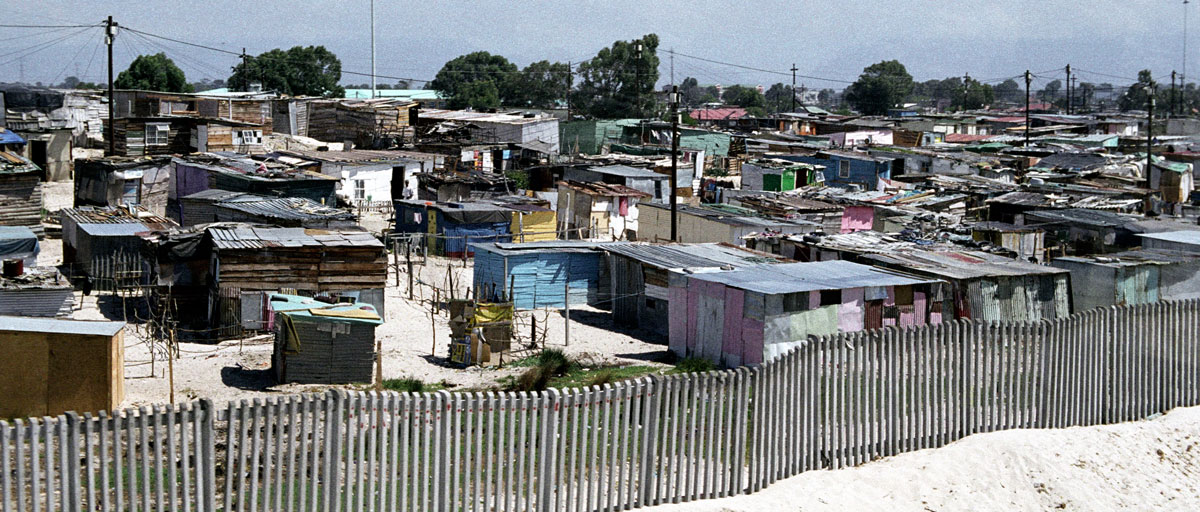

Bildtext får vara max två rader text. Hela texten ska högerjusteras om den bara ska innehålla fotobyline! Photo: B. Christensen/Azote

nature and mental health

It takes a bit of nature to remain sane

A framework to incorporate nature's impact on mental health into city plans

- There is ample evidence that spending more time in nature improves mental health outcomes but quantifying these benefits has been difficult

- An international research team, consisting of more than 20 leading experts from the natural, social and health sciences, has created a framework that can be used to incorporate these benefits into urban planning decisions

- Given rising mental health burdens and the costs they impose on society, the framework is a useful tool to know what kind of green infrastructures can best serve city residents.

Getting some fresh air surrounded by greenery can do more than just clearing your head, it might just keep you sane. A number of scientific studies have shown that nature experiences may benefit people’s psychological well-being and cognitive function.

But it has been difficult to find ways to quantify these benefits in a useful manner.

A new study published in Science Advances and co-authored by centre researchers Carl Folke and Therese Lindahl is an attempt to do just that. The international group of researchers have created a framework for how city planners around the world can start to quantify and account for the mental health benefits of nature and incorporate those into policies for cities and their residents.

Many governments already consider benefits that nature provide in cities with regard to other aspects of human health. But these actions typically do not factor in the mental health benefits that trees or a restored park might provide.

Carl Folke, co-author

Why city people need nature

The article provides a summary of evidence that demonstrates the positive correlation between mental health benefits and nature experiences.

For instance, studies have shown how spending time in nature, either individually, or in groups, enhances the performance of cognitive functions, memory and attention while also offering other psychological benefits such as increased social activity and feeling a greater sense of purpose and meaning in life. On similar lines, many studies have shown that nature experiences have helped reduce risk factors and disease burden for some types of mental illnesses such as depression.

Sadly, there is also a growing amount of evidence that modern lifestyles have led people to spend less time in nature especially as more humans now live in cities where the opportunities for experiencing nature are limited. This makes it more important for city planners to know the value of benefits nature offers; this is why the authors feel quantifying such benefits might aid effective decision-making when it comes to urban planning and design.

As Folke explains “Many governments already consider benefits that nature provide in cities with regard to other aspects of human health. For example, trees are planted in cities to improve air quality or reduce urban heat island effects, and parks are built in specific neighbourhoods to encourage physical activity. But these actions typically do not factor in the mental health benefits that trees or a restored park might provide.”

Four steps for informed decisions

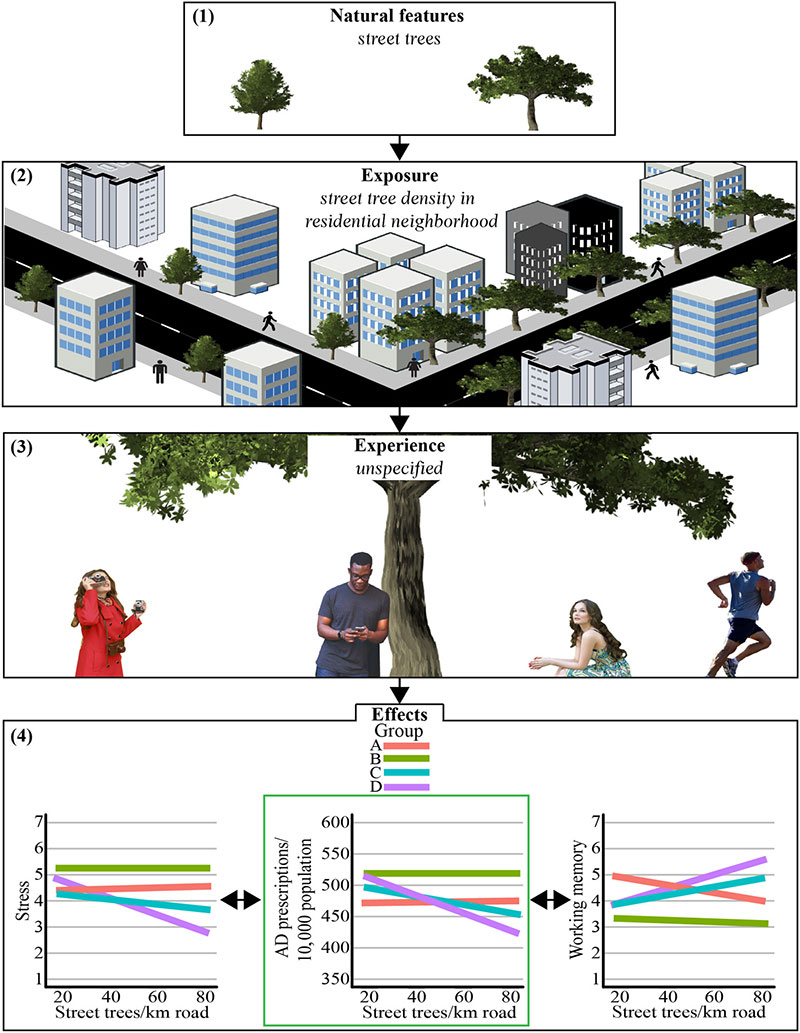

Given this context, the research team proposes a conceptual framework that can be used to make meaningful, informed decisions about environmental projects and how they may impact mental health. It includes four steps for planners to consider: elements of nature included in a project, say at a school or across the whole city; the amount of contact people will have with nature; how people interact with nature; and how people may benefit from those interactions, based on the latest scientific evidence.

The researchers hope this tool will be especially useful in considering the possible mental health repercussions of adding — or taking away — nature in underserved communities.

The authors conclude by highlighting that although there appear to be multiple limitations when trying to quantify psychological well-being, these are new and important research frontiers experts can explore.

As Lindahl explains, “Despite these limitations, we believe that there is a strong need for this type of conceptual framework. Planners and practitioners are increasingly demanding the ability to account for the co-benefits of green infrastructure and other choices related to the incorporation of green space in cities or increasing access to wilderness areas outside of them.”

A hypothetical application of the conceptual model using a case study for which antidepressant prescription is the outcome.Information is gathered for each of the three steps. (1) Natural features in this case are street trees (other characteristics unspecified, including spatial configuration). (2) Exposure is calculated using a cumulative exposure approach regarding residential street tree density (spatial configuration illustrated here for conceptual purposes but not relevant to this estimation metric). (3) Dose and/or interaction were not taken into account. (4) The effect of decreased antidepressant (AD) prescriptions in areas with more street trees is represented along with other potential benefits (e.g., stress and working memory) not projected specifically in this case, although they are represented conceptually.

Bratman, G.N., Anderson, C.B., Berman, M..G., Cochran, B. et.al. 2019. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Science Advances 24 Jul 2019: Vol. 5, no. 7, eaax0903. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0903